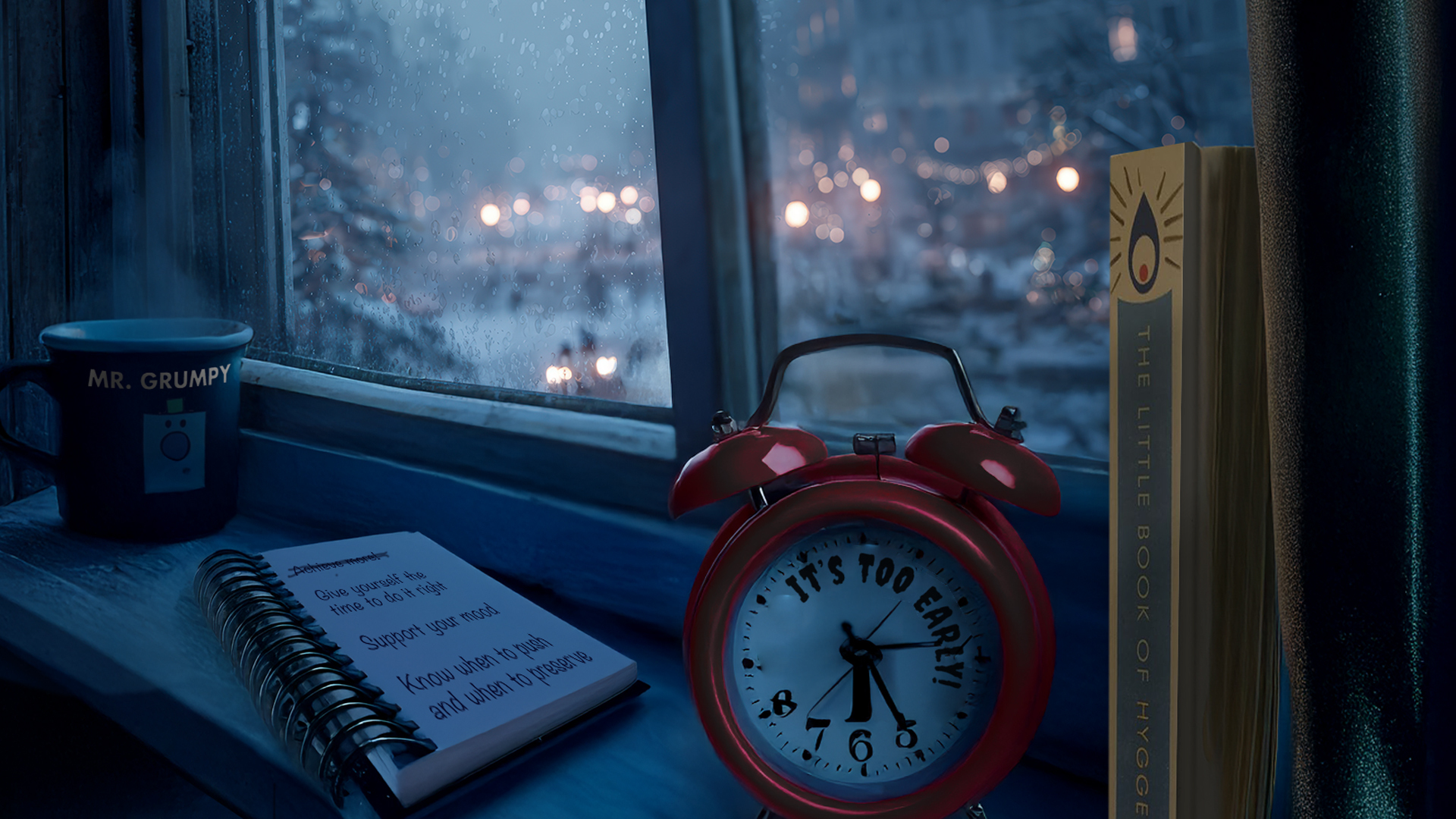

Winter has a way of exposing the limits of willpower. The days are shorter, energy dips, and the usual productivity narratives start to feel a little hollow. Rather than seeing this as a slump to fight through, we can choose a different approach, one that focuses less on forcing momentum and more on feeding the work, relationships, and thinking that genuinely sustain us.

When resources feel tighter — time, attention, emotional bandwidth — the question becomes less about what we can do, and more about what we choose to invest in. Some things quietly nourish progress and confidence; others simply consume energy without giving much back. Winter invites us to notice the difference, and to be more deliberate about what we feed, and what we allow to rest.

Things to nurture and things to avoid

We’re the only species that doesn’t formally act on the seasonality inherent in both our physiology and psychology — and even that’s too broad a statement. It’s mostly industrialised societies like ours.

In that context, steam power gave us two things. The first was a standardised clock, because railways needed timetables. Before then time was local and more personal — noon was when the sun stood highest over your head. The second was artificial lighting. Those combined to create a set pattern to every working day. The same start, and finish. The same outcomes expected.

To industrialists then as now, this seems totally rational. The trouble is it’s overriding an internal clock that varies between every human, and between every season. That biological clock runs a different algorithm, governed by an ancient logic: survival.

"There is only so long you can act as though a sunny Monday in mid-June is a dead ringer for a wet Monday in mid January."

Now, don’t come back at me with “Ah yes — and we all used to grow our own food, spin our own cloth and go to church on Sundays,” because I’m not talking about societal changes. I’m dealing strictly with biological imperatives, that simply can’t be re-coded over a couple of hundred years.

There is only so long you can act as though a sunny Monday in mid-June is a dead ringer for a wet Monday in mid January. If we’re smart, we’ll recognise different mandates and different restrictions in our mood, our emotions, and our thinking.

Because we’re writing for creatives like us, we’ll think about the habits that work best in summer, in winter, and maybe pause to think about the shifts between the two.

Three things to nurture

Dreaming + imagining | In winter we all find ourselves looking forward — to longer days, warmer temperatures, plants in leaf and bloom, winter birds leaving and summer ones arriving. That urge to cast forward, to envision, to dream, feels both natural and more profound in winter. Use it. Paint some hopes and dreams for the year ahead in broad brush and bright colours (metaphorically at least). The detail isn’t important — the intentions and direction of travel will endure.

Replenishment | The athlete in you already knows that fitness is as much about good recovery as intentional activity. The creative in you understands when that particular well is running dry too. Life has its demands, but knowing when and how to rest the creative muscle is important. In winter the biological signal for rest is at its strongest. For you, that might mean active recovery — working to a different rhythm or on different kinds of projects — or it might mean a real sabbatical. You decide, but don’t miss this opportunity.

Curiosity | Lots of words are expended describing the “barren landscapes of winter.” And they’re all wrong. There’s beauty in the silhouettes and stripped back nature of the season. Every estuary and shoreline is teeming with migrant birds. Winter’s low light and dramatic weather repaints forms and textures in surprising ways. Even on a wet afternoon in Newport! Winter is the season for the curious.

Three things to avoid

The overdoing-it to-do list | Admittedly, we love a to-do list at Cohesive. There’s a very blurry line though — hard to see and easy to transgress — between a genuine to-do list and a wish list. You’re not going to get through more than a handful of things in any one day, so keep it real. To help with that, and life in general, my habit (Andy) is to top my winter lists with “What can I do to support my emotional wellbeing today?” Hint: it won’t be by creating the world’s longest tick list…

Avoidance itself | Doing hard things is, well, hard. And in winter, potentially harder still. Just nailing the monster into its crate till another day isn’t necessarily going to give you peace of mind, in work or in life. What we’re not saying is “grow a backbone.” It’s more like: choose your moment, choose your helpers, choose to communicate your intentions. Then give it the time it deserves: do that one thing, one step at a time. Outside of life and death situations, there’s not too many things that won’t productively wait at least a short while.

Rigid rules | Declaring “I’ll go for a run/give up social media/post on LinkedIn every day in January” is a sure fire way to set yourself up to fail. Being more flexible gives you more chances of success.

Using your energy intentionally

Winter has a different rhythm, and most of us feel it. Energy is less abundant, thinking can be slower, and tasks that felt easy a few months ago take more effort. The temptation can be to override that shift — to push ourselves back to “normal” rather than respond to what’s actually available.

Accepting that winter energy is different isn’t a lowering of standards. It’s awareness. When energy is finite, force becomes a weak strategy. Discernment matters more: choosing where attention genuinely counts, and where it doesn’t.

"When energy is finite, force becomes a weak strategy."

This is where rigid resolutions often fall down. Tough goals assume consistency that rarely exists year-round. When we miss them, the result isn’t momentum but guilt and disengagement — a pattern many of us recognise, even if we don’t name it.

Intentions offer a more useful alternative. They’re quieter than goals, but often more powerful. An intention might be to protect time for thinking, to stay visible without overextending, or to prioritise work that energises rather than drains. These choices don’t shout, but they add up.

"Winter isn’t a pause button or a test of resilience, but a quieter invitation to choose well."

Being kind to yourself in winter isn’t about total hibernation: it’s about knowing when to push and when to preserve. Sustainable progress comes from rhythm, not constant demand.

With that in mind, the question becomes not what you should be doing this winter, but what you’re choosing to nourish — and what you’re ready to let rest.

Winter isn’t a pause button or a test of resilience, but a quieter invitation to choose well. Feed what sustains you, rest what needs it, and trust that progress made in rhythm tends to last longer than progress made under pressure. Being kind to yourself isn’t a nice to have. It’s strategic.

What do you think?