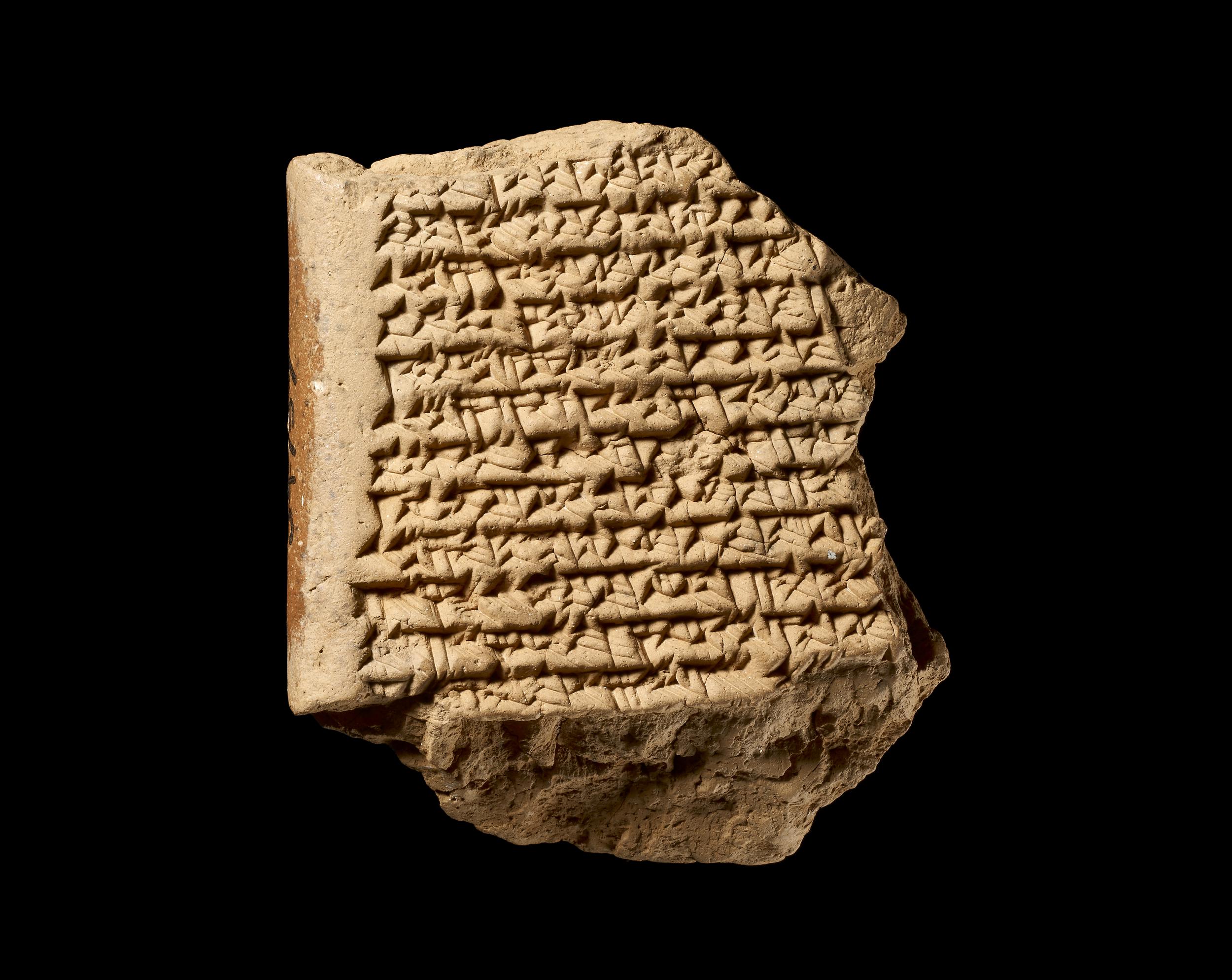

This unprepossessing lump, which would easily fit into your hand, is a piece of clay dug out of the ground between the rivers Euphrates and Tigris in the country we now call Iraq, some two and a half thousand years ago.

The bizarre marks are not the result of a pigeon walking across the surface of the clay, but characters, impressed with a piece of reed, encoding words in the Babylonian language. The text, which can be read, believe it or not, records the movement of Jupiter using geometric principles not known to Western mathematics until the 14th century. Besides what it tells us about the brilliance of Babylonian scientists, this piece of clay is a testament to the long history of human fascination with space.

For millennia we were content to sate this fascination by looking alone. But, like a child with dirty hands, we couldn’t help but touch. As we become increasingly aware of our impact on the planet’s resources, can we still justify a hands-on approach to space exploration? And what really motivates us anyway?

Galactic Britain

These questions were prompted by the recent news that the UK Government has drafted a space strategy and plans to launch satellites from Cornwall as soon as next year. Irrespective of politics, the announcement feels incongruous with news that living standards in the UK are declining and the shocking realisation that huge parts of the UK could be underwater if we don’t get a grip on climate change urgently.

There’s a huge amount of money in the space industry; in the UK it’s worth about £16billion, but it employs only 45,000 people – less than half the number of people who work in UK museums. So the question is, who is it really for?

Billionaires in space: vanity or insanity

Besides Britain’s ambitions to get amongst the stars, there is a wider trend of rich men, and it is mostly men, yeeting themselves into space for no other reason than, they can. The background to the billionaire space race begins with Peter Diamandis, co-founder of the International Space University, who launched the Ansari X Prize. The prize, worth $10million, was designed to spur the development of lower cost space travel and make it commercially viable. Since the prize was founded, Richard Branson has launched his space travel company, Virgin Galactic, followed by Jeff Bezos’ Blue Origin, and most recently Elon Musk founded SpaceX.

Undeniably, there is a degree of one-upmanship at play behind this race, just the three billionaires jostling for position on the rich list, they are competing with each other to build the biggest, be the first, go the furthest. There is something sinister about this in itself; a whole industry being created to settle a score between three of the most powerful men in the world.

But there’s even more going on. For the likes of Bezos, as the idea of a quick jaunt into space becomes ‘normal’, he has become increasingly vocal about his vision for populating other planets. He once commented; “We can have a trillion humans in the solar system. Which means we’d have a thousand Mozarts and a thousand Einsteins. This would be an incredible civilisation.”

Spouse of a NASA flight controller, Sim Kern, hits the nail on the head in this article in The Salon:

“So when you understand the science, it becomes clear that the ‘billionaire space race’ is just that—nothing more than a pissing contest between egotistical robber barons. Branson and Bezos aren’t investing their money to forward science or expand the bounds of human possibility.”

Expanding human presence in the solar system

Even if we find this idea of colonizing neighbouring planets whilst our own burns somewhat distasteful, would it even be possible? Kern again provides an answer in the same article:

“The International Space Station crew is only able to survive up there at all because multiple countries employ thousands of brilliant, highly-trained engineers and doctors and astrophysicists and computer experts whose full-time job is keeping them alive and the ISS functioning.”

In short, the amount of Earth-based infrastructure required to keep a dozen or so astronauts in space means it would be impossible to sustain any substantial population in space. After all, “space wants to kill you.”

So there’s a broad consensus that rich, powerful men in space is a vanity project, what about national space programmes; NASA, or Galactic Britain for example? NASA, who to be fair to them, know more about space travel than I do, helpfully provide an answer to the question “why we explore” on their website. Essentially their response boils down to “because we’re curious and we can”. But does this really justify a space programme?

Enter Growth. Or Progress. Or Development. This is the line of argument those who are pro space exploration draw first. Society has forged a cast-iron bond between technology and progress, that leads us to believe that more is always better and that if only we keep investing in technology it will come to save us. But, the numbers just don’t add up. Professor Tim Jackson summarises the debate around growth in this article in The Conversation:

“Ever since 1972, when a team of MIT scientists published a massively influential report on the Limits to Growth, economists have been fighting about whether it’s possible for the economy to expand forever. Those who believe it can, appeal to the power of technology to “decouple” economic activity from its effects on the planet. Those (like me) who believe it can’t point to the limited evidence for decoupling at anything like the pace that’s needed to avoid a climate emergency or prevent a catastrophic decline in biodiversity.”

The long and short of it is, humanity already has a presence in the solar system; the little blue ball we call Earth. Doesn’t it make sense to address some of the problems here before we “spend trillions of dollars littering our techno-junk around the solar system”, to quote Professor Jackson.

Space junk

Just what is the scale of the space junk problem? At the last count, there were over 20,000 pieces of debris in orbit larger than a basketball, and millions more of smaller pieces. And that’s before space tourism has even begun.

The final frontier

The last words go to Professor Jackson: “But for all its glamour, the ‘final frontier’ is at best an amusement and at worst a fatal distraction from the urgent task of rebuilding a society ravaged by social injustice, climate change and a loss of faith in the future.” Is it bold to go? Or would be bolder to stay and face our problems head on.

What do you think?